Types of Ambiguity

It was 2009, and I was struggling to get to grips with the literature around digital literacy. It seemed somewhat disparate and not at all cohesive, despite authors using similar terminology. What one author meant by ‘digital’ wasn’t what another meant by the same term.

Thankfully, a chance visit to a shop for remaindered books helped me enormously. There, on a shelf of this discount bookstore, was a reprint of a book from the 1930s by William Empson. Entitled Seven Types of Ambiguity, it was a work of literary criticism providing a basis for understanding how there are different forms of ambiguity. All I had to do was apply it to my own field.

Although this took slightly longer than I thought, and involved some wonderfully interesting detours, I was delighted when my post-it notes, mindmaps and crazy drawings coalesced into something that I think is worthwhile. My breakthrough came when I gave up trying to come up with one overarching definition of a single ‘digital literacy’. Instead of trying to avoid ambiguity I embraced it as an inevitable feature of human discourse. I came up with a continuum of ambiguity.

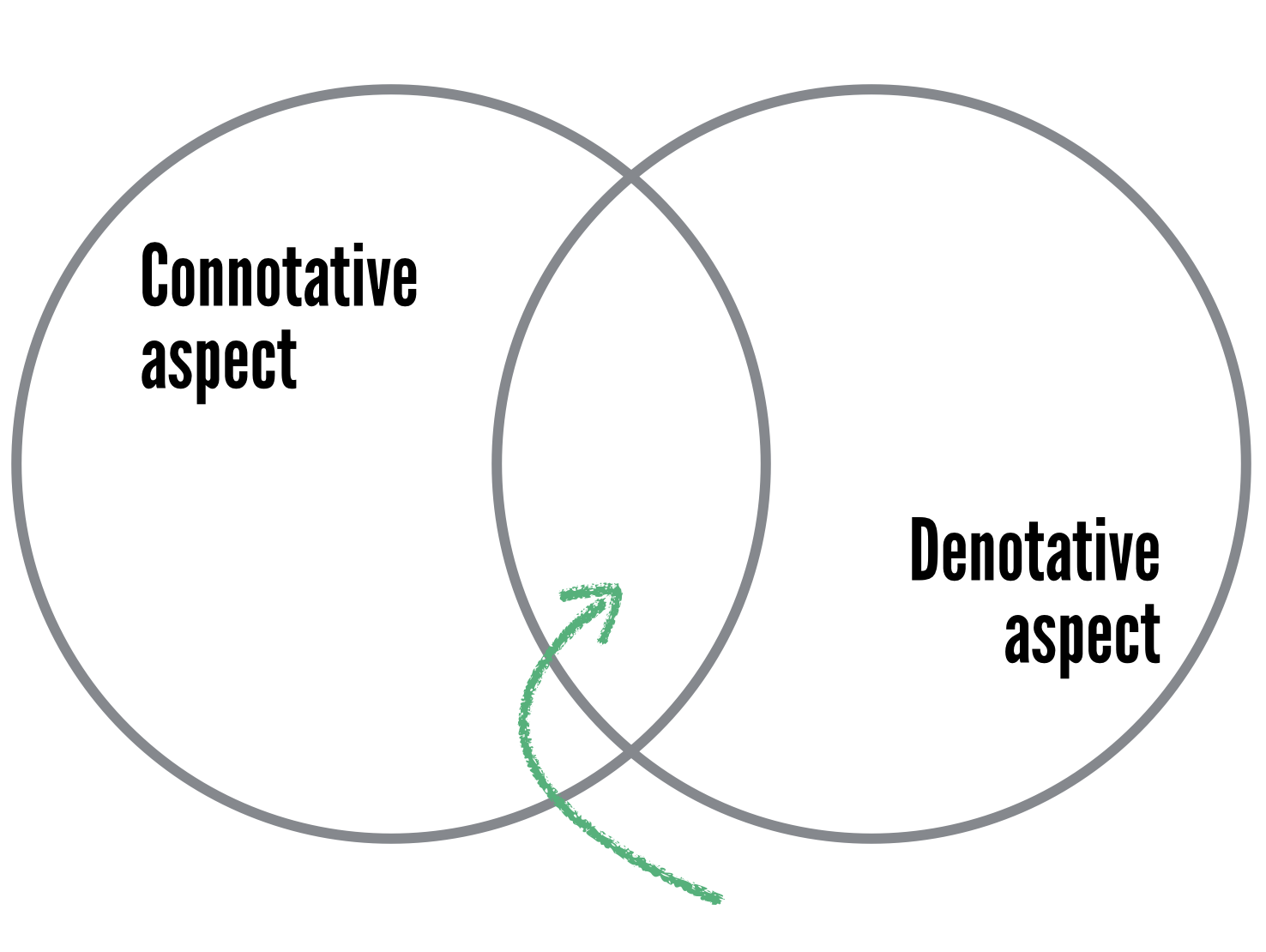

Before jumping straight into explaining the continuum, let me give some background by way of explanation. Every term that we use has both what’s known as a denotative aspect and a connotative aspect. The denotative aspect points to the surface-level meaning of the term whereas the connotative aspect points to its symbolic meaning.

So, for example, when I say ‘chair’ the surface-level (denotative) meaning might be ‘object with four legs upon which people sit’. The symbolic meaning of a chair (the connotative aspect) might be ‘this is somewhere I can sit down’. Because we can never know exactly what other people are thinking, we can never deal in terms that are purely denotative; there will always be some symbolic aspect to what we say or write down. Continuing the example, you might see the presence of a chair as an expectation for you to sit down. You may see this as something to do with a power relationship. The other person, meanwhile, could be blissfully unaware of this connotation.

The diagram below shows the overlap between the denotative and connotative aspects of terms that we use everyday:

It’s the middle bit of this diagram that interests us. That’s the bit where normal everyday human communication takes place. Towards the left of that overlap is conversation about ideas that are more abstract. Further to the right are discussions about more concrete matters. Note, however, that because of the reasons given above, you can never be absolutely certain that you’re talking about exactly the same thing as another person. People see the world differently.

If we consider that overlapping area in the diagram above as a continuum from more abstract to more concrete then I think we can divide it loosely into three distinct areas:

- Generative ambiguity

- Creative ambiguity

- Productive ambiguity

The first of these areas, Generative ambiguity, includes the types of terms and ideas dependent upon tenuous links. No aspect of the term or idea is fixed or well-defined. Terms and ideas within Generative ambiguity are one step away from being vague. The Oxford English Dictionary defines ambiguity as the ‘capability of being understood in two or more ways’ whereas if something is vague then it is ‘couched in general or indefinite terms’ being ‘not definitely or precisely expressed’. There’s a subtle difference between these terms, but I would suggest, whereas we might want to embrace ambiguity as a fact of life, we should avoid being vague.

An example of Generative ambiguity would be the kind of blue-sky thinking that leaders tend to do. Let’s use a digital literacies initiative within an educational institution as a homely example. One day the Principal of the institution might have a flash of inspiration due to the coalescing of an idea from a conversation she had the night before, along with the strategy paper she’s writing. It might be difficult for her to explain her vision to others in precise terms, but that doesn’t mean that it isn’t a good idea. It just means that she needs to work on the idea to express it in terms that will make sense in her particular context.

Once the Principal has done this, once she has started using the language of her immediate peers — which might be the rest of her senior leadership team — then she is in the realm of Creative ambiguity. Here, one part of the term or idea is fixed and well-defined. It is similar to a plank of wood being nailed to the wall near one end and allowing 360-degrees of movement around that point. When we’re talking about an initiative around digital literacies this might mean deciding what they’re talking about when they’re talking about ‘digital’. In their context, for example, this might mean ‘computers’ or ‘the learning platform’. In another context it might mean ‘anything electronic’.

Finally, we have the area I call Productive ambiguity. This part of the continuum involves terms and ideas of the least ambiguous variety. Examples here include everyday metaphors and one idea serving as a convenient shorthand for another. So when the Principal of the educational institution, along with her senior leadership team, present the idea to staff they’ve defined the broad parameters for engagement. They might, for example, decide not to call the initiative a ‘digital literacies’ initiative because of a previously-failed venture. Alternatively, now might be a very good time to call it a ‘digital literacies’ initiative as the institution can build upon the zeitgeist, a swell of coverage and interest by the media.

It is worth noting that terms and ideas can eventually lose almost all of their connotative aspect. These terms ‘fall off’ the spectrum of ambiguity and become what Richard Rorty has termed ‘dead metaphors’. These terms are formulaic and unproductive representations of ideas that die and become part of the ‘coral reef’ upon which further terms and ideas can depend and refer to. Invoking terms such as these tends to be avoided due to over-use or cliché. The terms usually cause people to roll their eyes when they hear them, or to say them with a smirk. ‘Digital natives’ would be a good example of this. It signifies nothing useful, not because it’s overly-ambiguous, but because it’s overly-specific and references an outdated way of looking at the world.