Skills are learned in isolation

I’m a firm believer that learning requires a context. In fact, I’d go so far to say that attempts to teach skills in a contextless way are not only doomed to failure, but that any supposed ‘successes’ using such an approach iare indistinguishable from charlatanism.

I can still remember a conversation I had as a student teacher with an in-service trainer. His argument was that skills were all that mattered and the rest was just ‘content’. My counter-example, as a History teacher, was the Holocaust. Surely teaching the actual events of the persecution of the Jews under Hitler’s regime matters as much as the ‘historical skills’ being developed. He disagreed, stating that any genocide would work equally well. At the time I didn’t know what to say; he was just plain wrong.

Like all good rebuttals, mine came to me about five years after the conversation. Once I had established myself as a teacher, I could see in practice that skills are not learned in isolation. A trivial example of this would be the very real example of 11 year-olds being able to draw a graph when sitting in a Mathematics classroom — but not straight afterwards in my History classroom. This problem seemed to be independent of which teachers and classes were involved; it wasn’t just my poor teaching! If the Mathematics skills had in fact been separately from the content then learners would have had no problem transferring their skills to a new context. Context matters.

When I’ve thought about it a bit more, the way that we are able to eventually separate skills from their contexts is through pattern-recognition as a result of immersion. We know that the best way to learn a new language is to move to the country where it is spoken natively — to immerse yourself in the language and culture. In other words, the best way of learning hard skills (vocabulary, syntax, pronunciation) is constant practice within a relevant context.

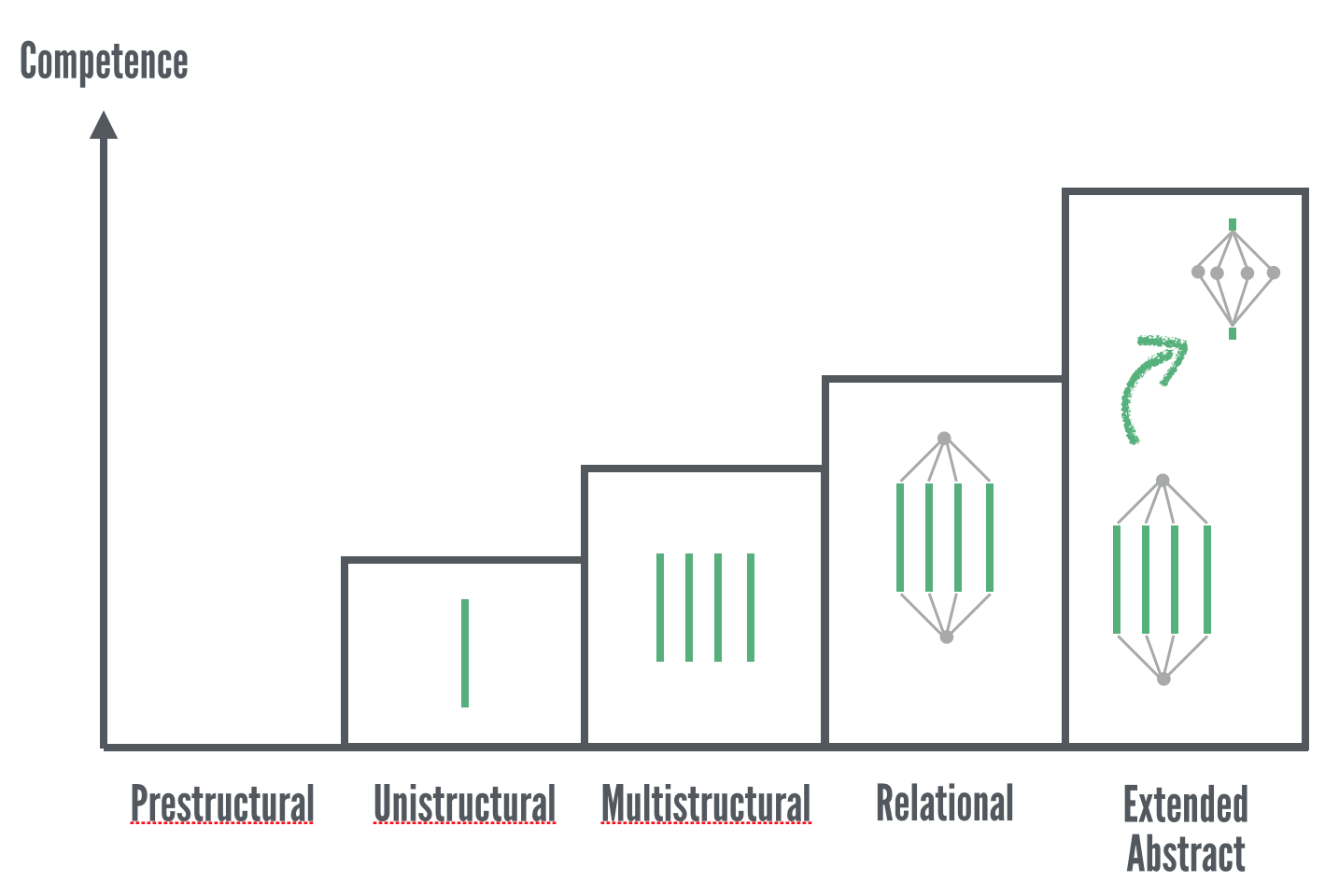

When presented with something for the first time it’s almost impossible to learn the skill independently from the context in which it’s performed. 1 We learn in a concrete way first and can only abstract from this later as we become more proficient. The Structure of Observed Learning Outcomes (SOLO) taxonomy helps to explains this development:

Based on: http://www.johnbiggs.com.au/solo_graph.html

In this representation of learning, individuals move from a ‘Pre-structural’ conception through to an ‘Extended abstract’ understanding. That is to say learners start off not really understanding, then focusing only upon one relevant aspect before slowly making sense of the various facets of the topic/area. Finally, the relations between the various parts is fully understood and can be generalised to a new topic or area.

This is all well and good, but how does this relate to digital literacies? Is the same true in the digital world?

1 A counter-example to this would be the ‘multi-skills’ classes that Primary school age children (including my son) do these days. Catching a ball is catching a ball, I suppose. I’d suggest, however, that muscle memory is of a different order to conceptual understanding.